Tschabalala Self’s art dances around the eye in the way feet must have moved to music in the Harlem Renaissance era. Exuding from her canvas and mixed media are chaotic and fast musings. It ’s a vortex of unabashed visions rooted in resilience, pride, and nostalgia. Her work brings forth an emotional, visceral, almost childlike appreciation in the viewer.

Are you supposed to laugh or cry? Is this you? “Do you remember that time?” I ask myself. Memories of my young black adulthood come flooding back while studying a drawn Presidente bottle in the Bodega Run series. Corner store crates and Goya products leave an imprint on the back of my darkened eyelids long after the original image has ceased.

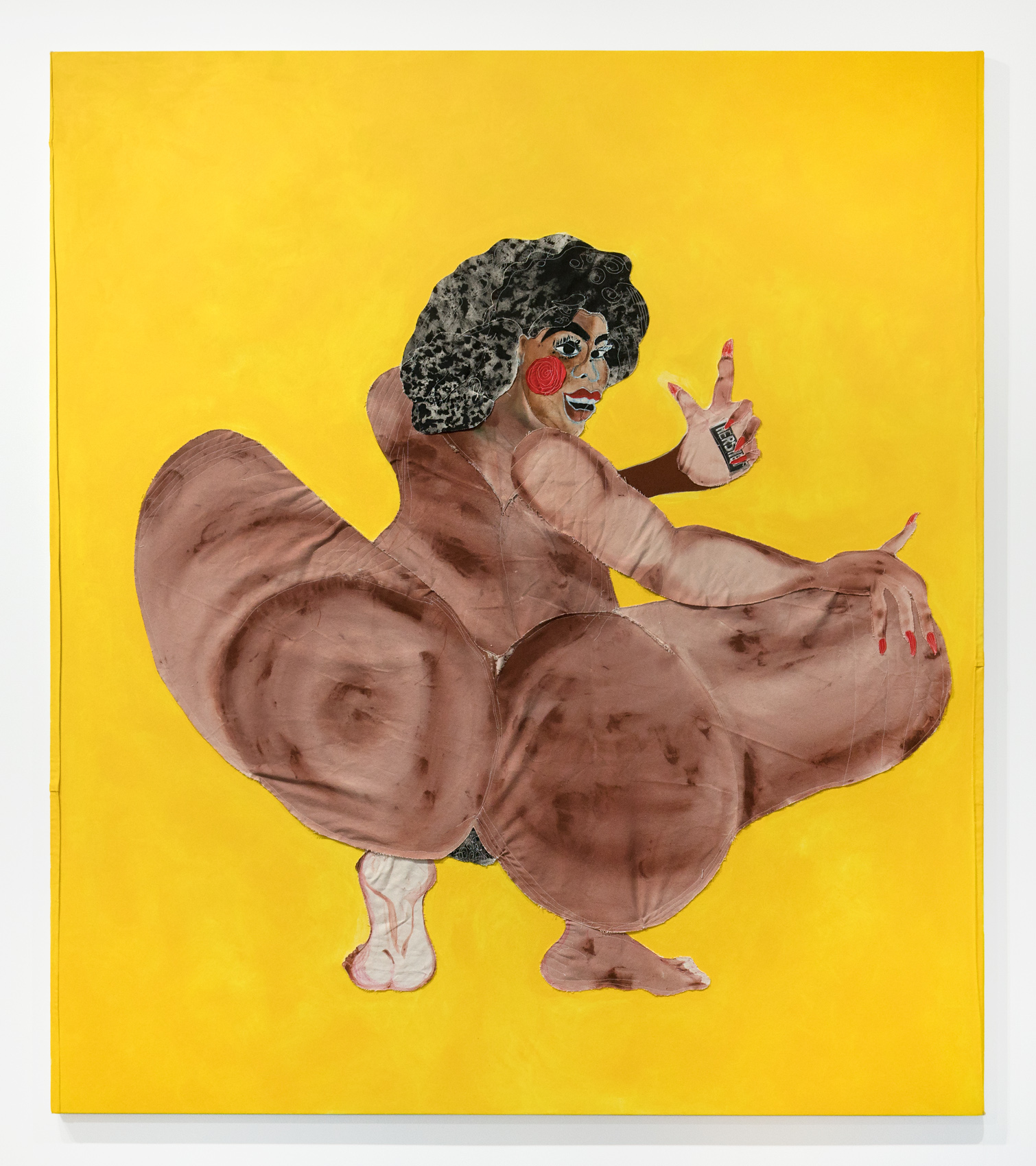

It’s an abstract-realism-noir approach to art that resonates but also delightfully confuses the viewer with its bright colors and middle-class signifiers. Tshabalala’s brush swirls and dances around topics like black women bodies–reclaiming as well as politizing them and in raw undulated primal snapshots.

It’s too easy to draw comparisons to Tschabalala and her contemporaries of the last century. She holds her own against obvious artists like Basquiat, Kara Walker, Warhol, or anyone else who might come to mind. There are references you can wander to but the biggest similarities are the excitement that the artist incites in the viewer from each of her works. Each stroke seems like it has to be followed, each bend of a plywood sculpture must be examined for all the messages laying within its curves.

The artist was born into a family that lauded art as a building block of education and communication. As a child, the young Self was in an environment that fostered her creative taking to’s. The family moved from New Orleans to New York because her dad got into Columbia’s MFA Writing program and from there, her creative heart flourished. She recalls having supportive mentors and stimulating environments throughout her youth in the New York City schooling system.

Milk Chocolate, 2017

“When I was in middle school at Wagner, it was really diverse. It was probably a quarter black, a quarter Latin, a quarter white, a quarter Asian. That was probably the best time I’ve ever had socially. Out of all of the schools, I went to it was the best social experience I ever had. That was a fun age to be around kids with so many different backgrounds. I just learned a lot about people. I had to go to prep school for high school. I was always well behaved in school, but then I began to skip out a lot so I got sent to a private school for high school. It was an all-girls school, a very small place on 91st street. That school environment was very conservative. I was very happy in retrospect to have that experience. It was a very good school, I learned a lot. I just learned how to function in that kind of space. It was a really good experience looking back now because now I have to deal with so many different kinds of people all the time, in the arts you have to do that all the time. My art teachers at my high school were great as well, and that school had a great program. I remember one of my art teachers there, Ms. Tobin, she was always playing NPR all day, all day, and I used to think that was so boring, but now I do the same thing.”

All her siblings studied art at different points of their life as well. One sister took to music, another sister studied film. Her brother wrote screenplays and her mom ran a program that trained women to join trade unions in New York.

“My mom very much believes in working with your hands and having a skill that you can have a career from that based on the work that you do with your body or your creativity. I think that’s why my parents emphasized I study art in school, especially my mom, she’s really supported me doing art, taking action, and studying it.”

Tschabalala Self- Princess, 2017; Pressed,2016

Her trajectory suddenly began to be groomed from a child that was interested in art to a modern artist developing intellectually nuanced work based on self-history and social studies. She studied at Bard and Yale for goodness sakes. Two thoroughbred institutions that have some of the world’s greatest thought leaders as alumni. I begin to gloat about her experience, what a prestigious education she has. She hesitantly stops me.

“I think that’s what everyone has in their imagination about those kinds of spaces, these ideas, even though they have positive connotations, complicate it when you’re a person coming from a marginalized community. In the back of your mind, you’re repeating the idea that this space is not designed for you. You have to have the balance, you can’t be so strong that you can’t shift. Artists have to be mutable to really be strong, you have to be able to change and evolve. You know, there’s this kind of Stockholm thing that happens when you’re in grad school, this really weird…it’s kind of removed from a normal lifestyle, so removed that everyone that’s in that environment is important, magnified, their opinions are magnified, all your emotional things are magnified in that environment. And then all the people who are given power within that context, are magnified. The way in which you’re absorbing that information, it doesn’t translate into reality. It can be kind of strange but I did get a lot out of that experience.”

Whilst at graduate school in Connecticut she felt that there was a problem in the way she was to tie every black female body to an association in which a black girl has been exploited in the American context. The artist had concerns about this as well as the access to her work by the people who needed to see it. Being insulated in such elite environments doesn’t exactly lend itself to a diverse following.

“If I’m making work about voluptuous black women that work cannot be seen in the same way that an older painting is of a white woman, there’s no possibility almost that these personas have a sexuality that exists outside of a vacuum of the gaze that was acknowledged by the white male. Which was the same as being viewed as the subject? So that was one of the things that were difficult for me working within the institution with my work. I thought for a long time I would have those same problems if I started showing outside, showing the art world or showing outside of school, but those conversations actually didn’t happen as frequently as I thought.”

Tshabalala’s art pushed these conversations from reductive to reactive. With that came a wide net of fanfare all over the world that met her with acclaim and intrigue.

“I’m very thankful for that,” She says of her success. “That makes me feel very much encouraged that I’m communicating strongly with the work and I’m communicating sincerely. Black women are my ideal audience for my work, they’re kind of the motivation for creating the work. But I feel like if you’re creating something, anything, and it’s truthful, all people no matter where they’re coming from should be able to identify with it.”

The black woman is no doubt her muse and making images that speak to the experience of being a black woman or being a black identified person in a social and historical context is her fodder. Her work has been viewed at museums, galleries, and fairs from Tel Aviv to Brooklyn. Her rich patchwork of techniques and mediums are art collectors ready and have cemented her narrative in a part of the larger quilt of American history. Her work is both culturally valuable and relevant because of its unapologetic mainstay of stories that need and should be told.

Tschabalala Self- Loner, 2016

Coat, Colin LoCascio. Top, Ph5. Belt, Off- White. Heels, Prada.

Left to Right: Tschabalala Self- Sunday, 2016; Sapphire,2015; Swim, 2016

“I wanted to create work that people from my community could see and it could resonate with them and they could see themselves within, I think it’s important to have representation. I feel like black women should be autonomous, it is no good or bad. I feel like a lot of times black women are like, you have to act like this or be like this or don’t be too loud… but autonomy is everything, you’re allowed to be yourself and everyone should be viewed. I love that about black Americana or being black in an American context, the things that are highly dysfunctional are also the things that are the most interesting about this nation. A lot of things come across as dysfunctional within the black community, I think this is why it’s so difficult for black artists to make work about our community because there are so many things that are so beautiful but they do come out of social circumstances. So if you condemn all of the social circumstances that exist from our community than you’re condemning all of the beauty. Instead of making sense of sensibility of it then the work is forever tied to whiteness, our segregation, by always putting it in a historical context, I think it’s better to just make work about black life. It doesn’t have to be anchored in this way to our history which is- there are so many things that are obscured in our history, which is our history. I like that middle-ground, it’s in the middle-ground where I find a lot of inspiration from.”

Viewing Self’s work is emotional for that reason. She makes even the most problematic stereotypes beautiful, enhancing, and showcasing all sides with equal merit.

“I’m at the point where I find making paintings, I don’t think there’s any sense to try to define, to say this information is good, this information is bad. I find that did more damage. Information, just presents it and allow people to sit with it and digest it because at the end of the day if it’s bad or good, the information is out there, your opinion on it at that point is not the main priority. Also, I think that so much black art that I was seeing interacts with, or art by black artists, it either didn’t deal with these issues- not that it should- it had no responsibilities to, but if it did deal with these issues, it was always from the direction of trying to uplift black people which can often be very dangerous because by thinking about your work in that regard, you’re accepting this idea that you are downtrodden, presenting this belief that you are downtrodden. And to uplift, a lot of times when people say they want to uplift, what they’re really saying is that they just want to create this system in that black people are seen in the same way as white people, which is also problematic.”

With so much under her belt, it’s hard to imagine that the best is yet to come. Present-day Self resides in New Haven developing and building on her work with the same fervor that she had a child. It’s easy to imagine her tucked away in her studio with a variety of supplies yet to be transformed into another masterpiece.

Tschabalala Self- Pink Eye, 2015

Coat, Colin LoCascio. Top, Ph5. Sunglasses, Prada. Necklace, Model’s Own.

Coat, Colin LoCascio. Top, Ph5. Sunglasses, Prada. Necklace, Model’s Own.

Dress, Viva Aviva. Sunglasses, Vintage. Belt, Vintage. Necklace, Model’s Own.

Dress, Viva Aviva. Sunglasses, Vintage. Belt, Vintage. Necklace, Model’s Own.

CONNECT TSCHABALALA SELF:

PHOTOS / Christian DeFonte

STYLING / Colin LoCascio

MAKEUP / Natalia Lopez de Quintana

STORY / Koko Ntuen