story and photos / Maeghan Donohue

I stayed home the day after the election. There were two gears on social media amongst my leftist friends: Either they were positively suicidal or were condescendingly dismissive, claiming this isn’t a big deal, not that much will change. Neither of these were attitudes I was equipped to handle. With the future of the economy and rights of people of color, women, LGBTQ, and innumerable others hanging in the balance, I didn’t want to hear devastation echoing throughout the city when I was already devastated. But I also didn’t want to hear the widespread despair dismissed as an overreaction or the fallacy that things couldn’t regress much in four years. We already haven’t changed enough. There have been staggering numbers of hate crimes by civilians and by the police over the past few years—and this is only what has been reported. Reproductive rights have been quietly yet aggressively ravaged state by state. And this happening during the Obama administration. So what happens when we have a leader spewing hate on TV daily? How far will this set us back? Faced with such questions, the instinct to stay reclusive was strong. But damn it, I didn’t cancel my week. I went out two nights in a row to see the most inspiring musicians of my childhood play in New York City during a time when hope feels lost.

If you had asked me when I was thirteen who or what taught me the importance of politics and activism, I would have told you Ani Difranco and Bikini Kill. If asked now I would give a long and varied list. But not only would Ani Difranco and Kathleen Hanna of Bikini Kill still be on the list, that list exists because of them.

There are countless examples throughout history of art being wielded as an effective political tool to engage, organize, raise consciousness, and even indoctrinate. Music has been a particularly successful medium in terms of inspiring socio-political discourse and engagement. The immediacy of music, the ability to absorb it passively, and its relevance to so many historical eras are all reasons why it is such an accessible art form, and thus a successful conduit for politicization and activism. In diverse metropolitan areas or in havens like liberal arts universities we take for granted the ability to plunge into a vast world of conflicting concepts. But in the rest of America, access to certain thinkers, ideas, and even accurate historical knowledge is not a given. Growing up in 90s rural America before the internet made such huge strides in enabling the rapid proliferation of information, alternative viewpoints simply weren’t as available. In my conservative mid-Atlantic hometown there were certain books that were suspiciously missing from our school library, many teachers taught through a neo-conservative lens asserting their personal opinions as fact to impressionable students, and the town was so literally racially divided that a street which ran from the “white side” of town populated with large Colonial homes was named 5th Avenue, but changed to 5th Street upon entering the “black side” where public housing was situated. Needless to say, I did not learn about the pitfalls of a capitalist economy, the injustices of institutional racism, or the history of feminism in the classroom or the greater community. However, I don’t want to paint an entirely grim picture because I found many kindred spirits. When you are an obvious outlier in a community the magnetism to other like-minded people is powerful and profound, and this is ultimately how I politicized. My life changed when an 8th-grade teacher took an interest, befriended me, and gave me my first Ani Difranco CD, Living In Clip. This single gift changed the trajectory of my life and worldview.

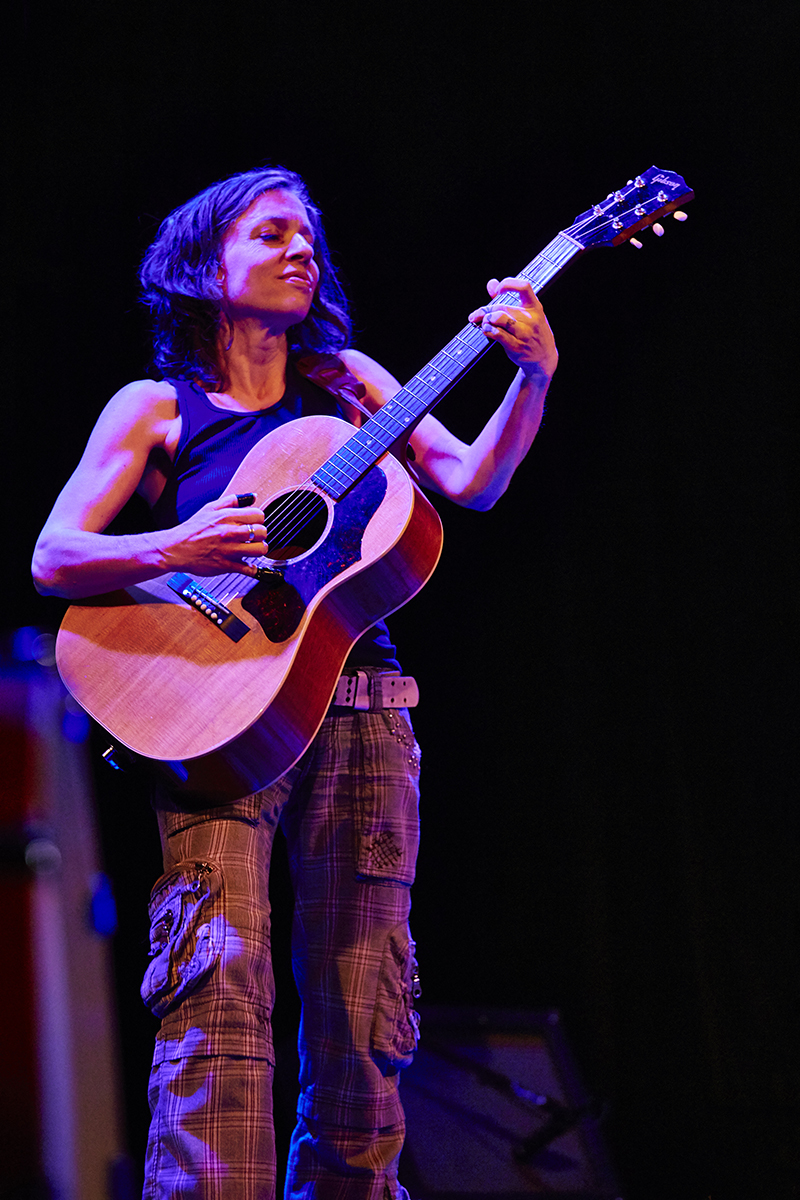

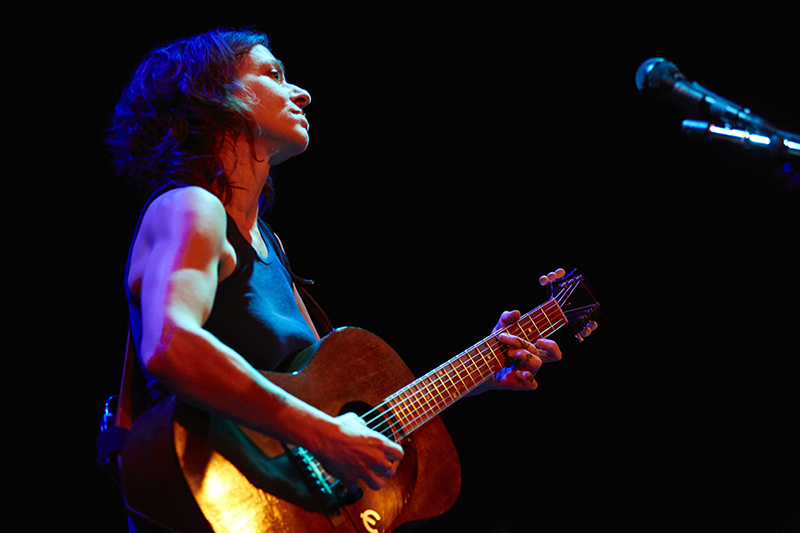

At that age what most appealed to me about Ani was the extremity of emotion—from elation to rage (relatable for any pre-teen girl!) when she tackled ultra-intimate subjects like heartbreak, resentment, careerism, and sexual abuse. I had never heard an artist so openly grapple with the traumas of being female, but also with economic and racial inequality, cultural appropriation, worker’s rights, reproductive rights, and innumerable other enclaves of social injustice. And her guitar sound—oscillating between melodic fingerpicking and heated hammering— sonically mirrored the complexity and conflict in her lyrics beautifully yet unsettlingly. Most important for me at the time was that she wrote about things no one around me was talking about. I may have heard words like feminist, had a general understanding of Reaganomics, or witnessed sexually inappropriate behavior from men, but these subjects were taboo. Sexuality was stigmatized, as was even the racial and economic inequality present everywhere in my town. Ani’s particular brand of outrage coupled with these topics was truly radical. The relatability of her motifs attracted me to her music, and then once I occupied that space, I gained access to concepts I hadn’t known or thought about previously due to my stifling context. Because of her songs I now had a preliminary vocabulary and could delve into the subjects that have ultimately driven my art and scholarship ever since.

It was while attending Ani concerts and engaging in her passionate, inclusive Righteous Babe community that I first learned about Kathleen Hanna, her band Bikini Kill, and the Riot Grrl feminist/punk movement. Ani and Kathleen are rarely discussed in relation to each other, presumably because they come from disparate music traditions (Ani from folk, Kathleen from punk) and thus have different audiences. There are notable differences in craft and delivery as a result, but Bikini Kill spoke to my angsty teenage soul via Kathleen’s screaming refrains, and what Riot Grrl stood for always seemed to me naturally adjacent to Ani and Righteous Babe. Like Ani, Bikini Kill and other bands in the Riot Grrl movement wrote about rape culture, patriarchy, racism, objectification, abuse and empowerment. By the time I heard Bikini Kill they had already disbanded, but I spent countless hours analyzing the music and reading Riot Grrl fanzines. I was moved by Kathleen’s energy, screaming anger, and girls-to-the-front mentality.

Both women gave me so much to digest, to be angry about, but also so much to be excited about. I suddenly had permission to express honestly —whether it be my opinions about the world around me, or personal issues like sexual desire, abuse, and abandonment. Simultaneously, because I had this newfound vocabulary and so many new themes to explore, I began exposing myself to artists and thinkers that weren’t taught in my school. I read about Karl Marx, Malcolm X, Gloria Steinem, Allen Ginsburg, Emma Goldman, Simon de Beauvoir, Ralph Nader, Howard Zinn, Angela Davis…and on and on. Every book, every thinker, every area of study begot another. Ani and Kathleen merely scratched the surface of significant issues in the realm of social justice and personal expression, but they pointed me in the direction of who and what I needed to be learning.

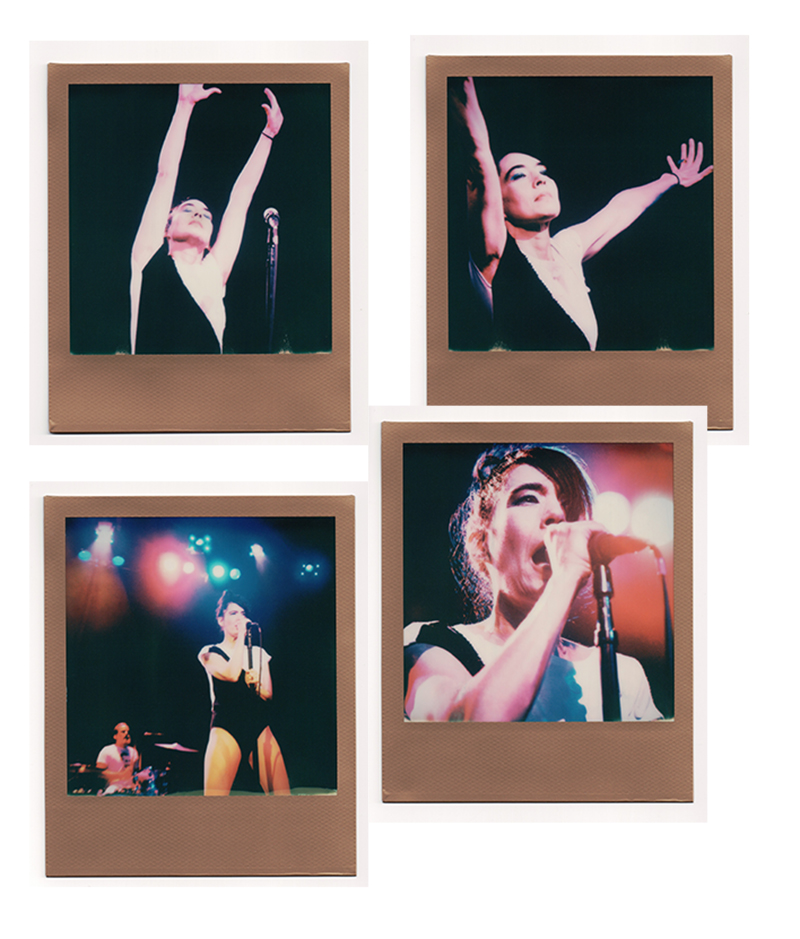

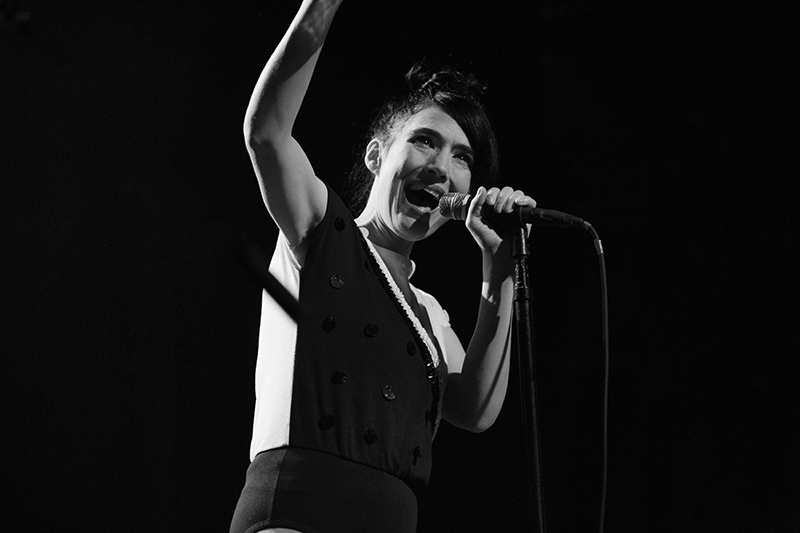

Each one of Kathleen’s bands since Bikini Kill split has had an entirely different sonic sensibility, but there is a constancy to Kathleen’s lyrical themes that demonstrate a certain fidelity to that old school Riot Grrl. When she came onstage at Irving Plaza last Thursday with her most recent music project, The Julie Ruin, she had tears in her eyes as she addressed the audience: “We need you. You need us, but tonight, we need you too”. But then the music played and Kathleen danced and sang with the vibrancy of a teenager and the crowd jumped and screamed so severely that the floor shook. Suddenly everything felt a little better.

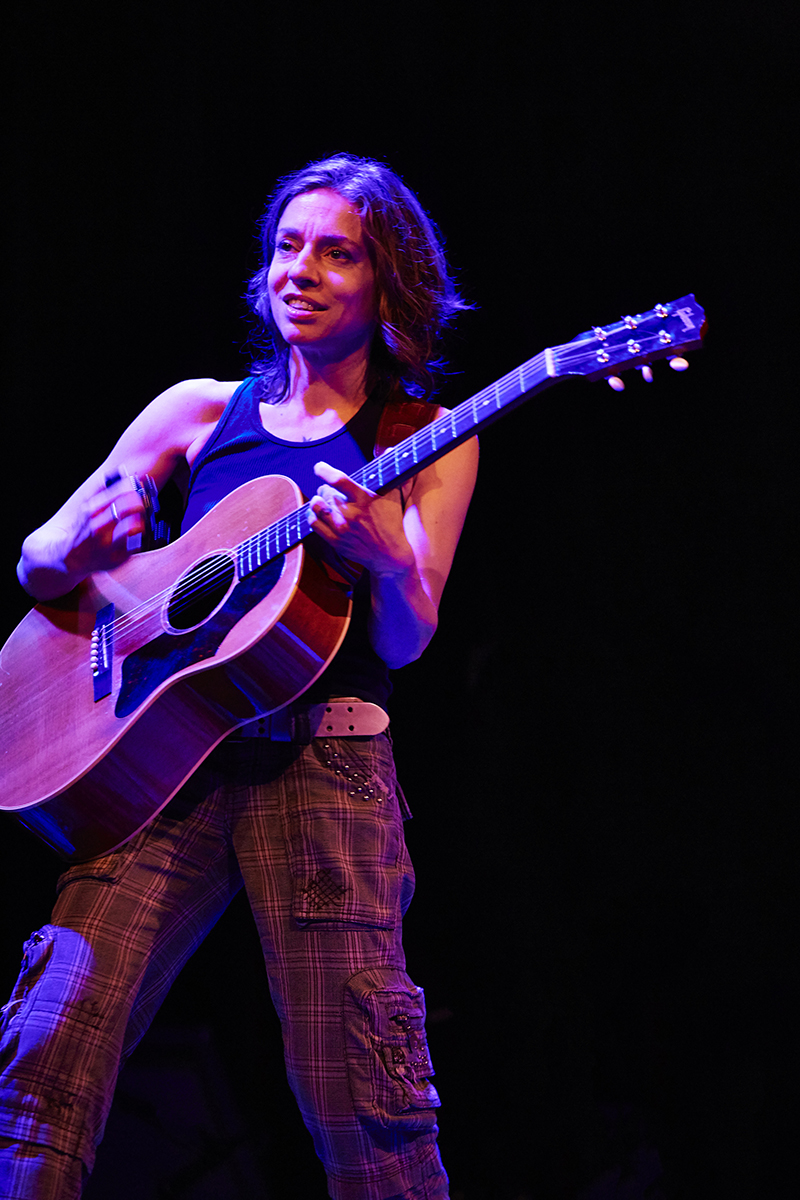

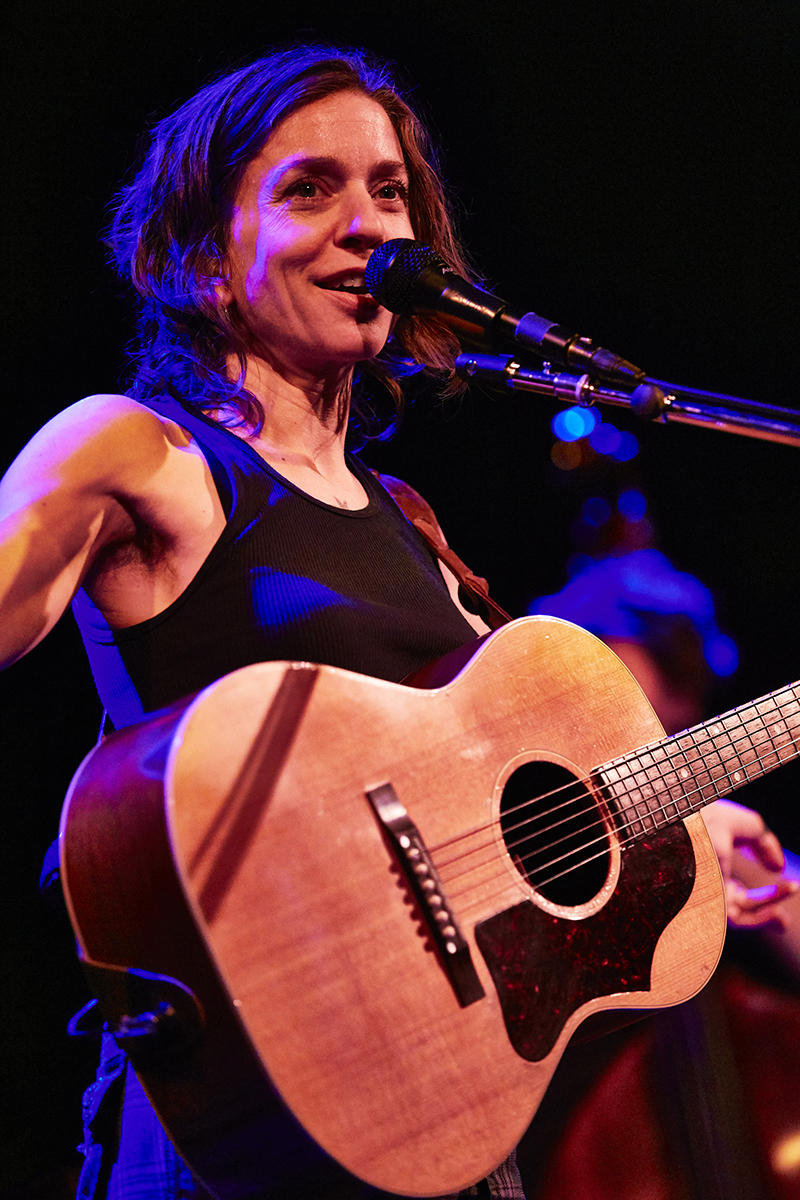

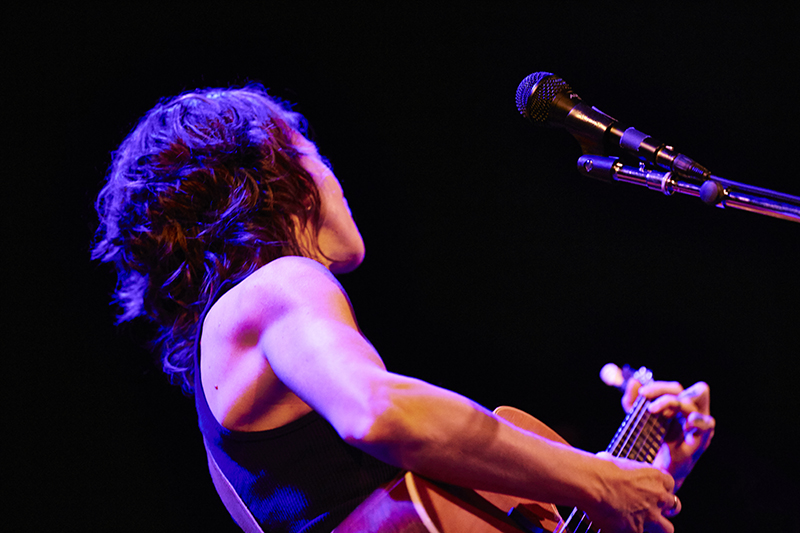

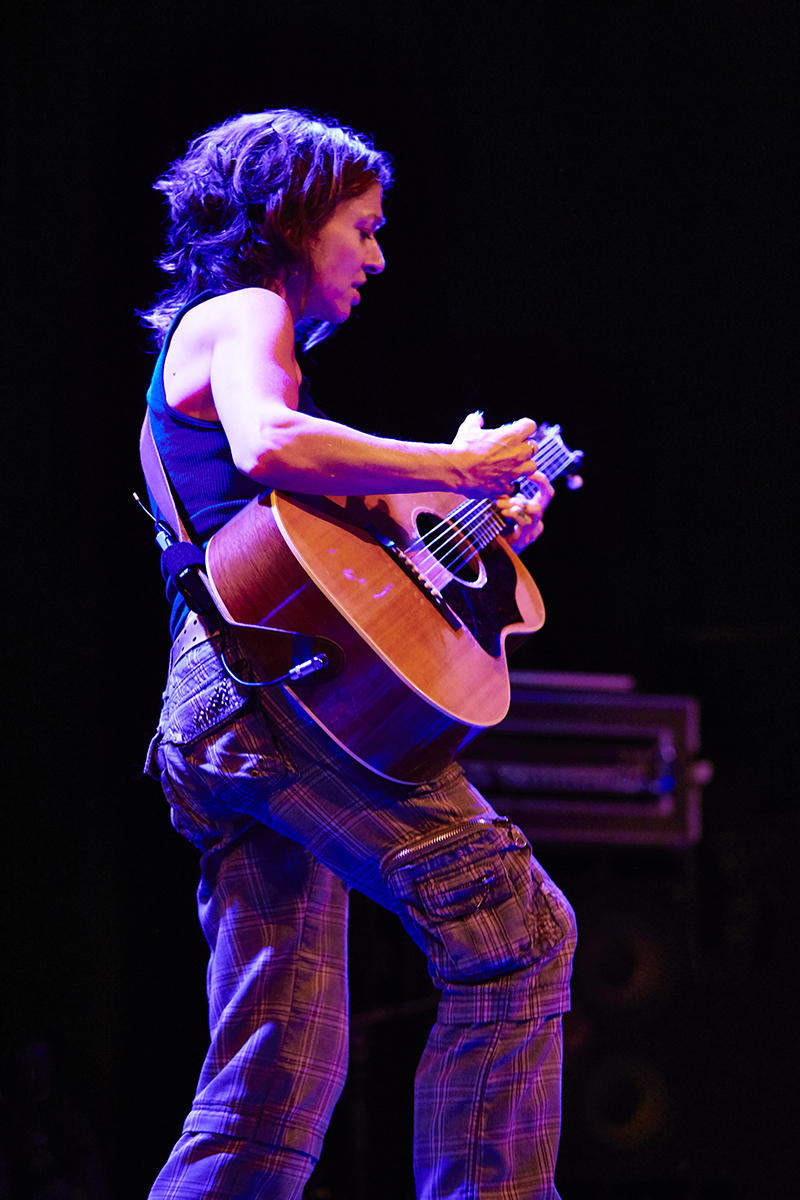

On Friday night at Music Hall of Williamsburg Ani had a strange sense of calm when she took the stage. “Of course I know I’ll have to write all new songs…” she said laughingly to the crowd. “…But lucky for us we survived eight years of George W. We’re going to have a sick sense of humor by the time this is over.” She addressed her audience between songs with her typical themes, most notably the inequality produced by the constructs of race, gender, and capitalism. But during this performance, in particular, there was an increased emphasis on community. “Wouldn’t that be great, if the whole show could have one big group hug?” The crowd roared when she recited her poem “Coming Up” which she prefaced by saying was written in NYC in 1990 but is even apter today, alluding to our president-elect. The show was spirited and hopeful, but also a serious call for action. She played old songs of protest and a few new ones including Play God, the single she released last month which rallies against patriarchy and the co-opting of the female body. This is a crucial song in a climate where our reproductive rights are once again eroding. Ani’s voice feels as strong and relevant a feminist voice as ever. Here’s hoping that a new generation will listen.

The realm of music is the only place where certain ideas could reach me in my youth, germinate, and prompt self-directed research outside of the conventions of my context. And my situation is not particularly unique. In rural America, the suburbs, even in disenfranchised neighborhoods within cities, certain contexts actively regulate what information and ideas are accessible—even with the internet as part of daily life. Music has always found a way to proliferate. Many people tell me deeply personal stories about how Hip Hop or Rock did for them what these feminist/activist musicians did for me, illustrating that regardless of genre, music has the potential to reach and transform. But the outcome of this election is dangerous. This outcome makes me fear state-imposed censorship, infringement on our rights to free speech, and potentially losing our access to information and ideas, even in a place like New York City. It makes me fear losing art and music and the freedom of any personal expression that isn’t aligned with the impending political regime. The outcome of this election has taken me back to thirteen, feeling stuck and frustrated and knowing more was out there, but banging my head against the wall, unable to access what I wanted because I didn’t know where to look or what questions to ask. Now I feel stuck again—this time as a citizen in a stagnating nation, forced to confront the overwhelming amount of ignorance, racism, greed, and xenophobia that we keep denying exists because it’s 2016 and we thought we’d be further along.

Let’s hope that even in this climate we still have the resolve to keep making art, to keep making music, to keep reaching people who might simply not know any better, who might not have access to an alternative view. This election has been such a blow to progress, and we need to get angry and then be productive with that anger. To simply despair isn’t the solution. But to cavalierly dismiss fear and despair isn’t the solution either. We have to keep producing passionate political art and disseminating progressive ideals—Malcom X said it best— “by any means necessary”. We can’t expect people who don’t have the access to knowledge to somehow learn without any direction. We have to give them the tools to ask the vital questions. And in the words of Ani, “Every tool is a weapon if you hold it right”.

When all else failed last week, it was comforting to remember the power of art and music. It was comforting to turn to the two women who first got me unstuck. Ani, Kathleen: It’s kismet you came this week. You’ve been fighting the fight for a long time, I know you’ve got to be tired. But thanks for still being here.