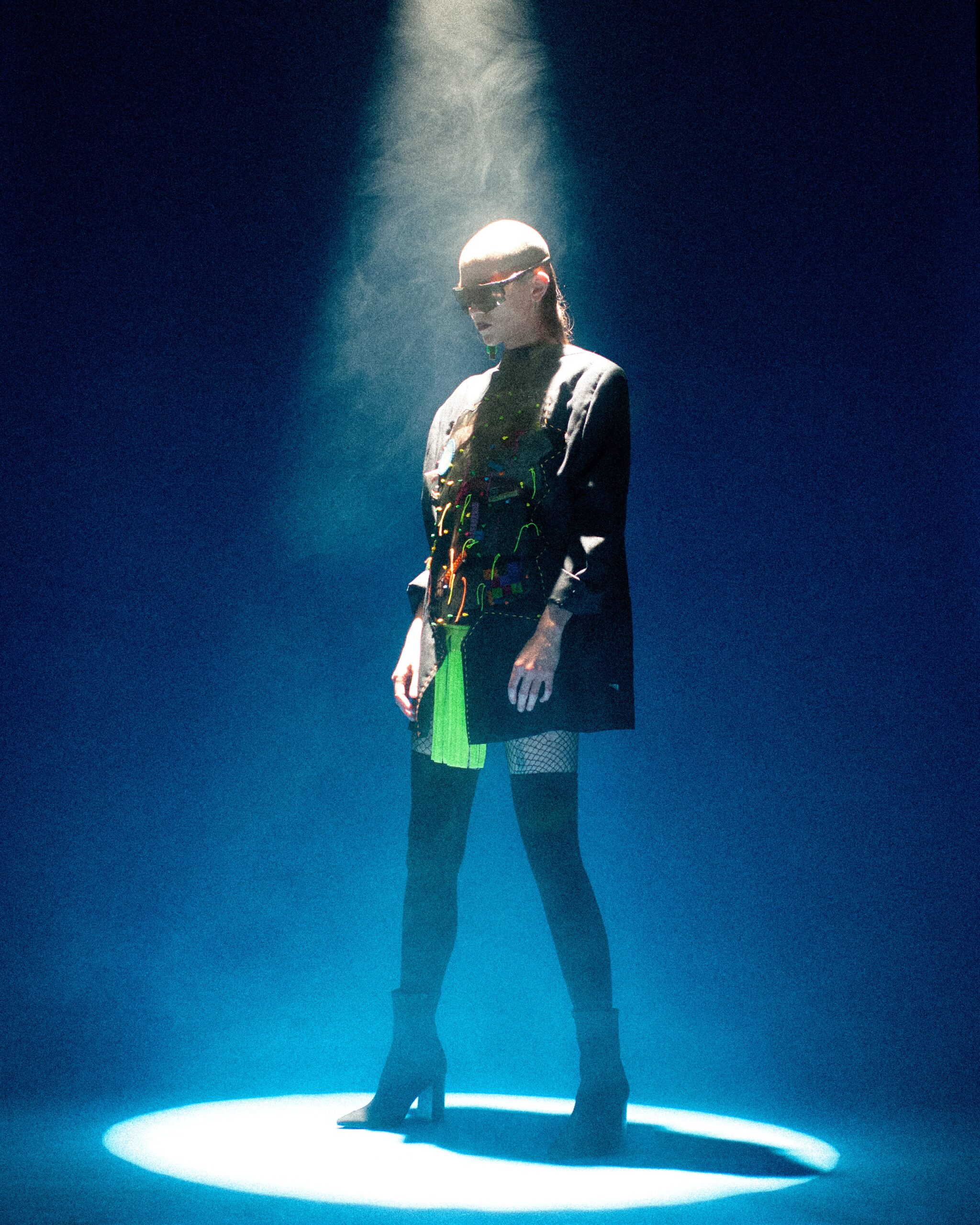

AC Carter, better known as Klypi, is a rising artist blending synth-pop, performance art, and visual design into a unique, genre-defying expression. From early experiences in experimental noise bands and visual arts, Klypi developed a bold, multidisciplinary style that challenges norms around identity, emotion, and resilience.

Their sophomore album, Icon Enterprises, explores complex themes like unrequited love, abuse, and digital isolation through catchy yet thought-provoking tracks. Marking a significant career milestone, Icon Enterprises also critiques the capitalist and social structures of the era.

As Klypi continues to develop new projects, the message remains clear: be unapologetically yourself. Through Icon Enterprises and beyond, Klypi not only invites fans into a world that blends the nostalgic with the contemporary but also provides a safe space for self-expression, critique, and personal exploration.

We sat down with Klypi to discuss the journey from introspective beginnings to the creative vision behind Icon Enterprises. In our conversation, Klypi shared insights into how performance art has helped confront insecurities, how the character of Klypi allows for the exploration of gender and emotions in ways that traditional roles might limit, and how the album’s songs reflect their personal experiences with isolation and resilience. By channeling these emotions into music and visuals, Klypi hopes to connect with audiences who share similar struggles, offering a reminder that embracing one’s unique identity is an act of strength.

You started out in music in a way that’s pretty different from what you’re doing now with Klypi, going from singing in the shower to being in a noise band to now building your own sonic universe. What events or experiences were crucial in guiding you to this very personal and multidisciplinary style?

AC: It’s a few things. There is a misconception that performers are natural extroverts. Performing was and probably still is the least natural thing for me, but something about that made it exciting. I was pretty shy in grade school, and I didn’t write music. I listened to and sang along to plenty of songs, though: RENT was on heavy rotation in that said shower! My mother, who is a great singer, always told me I had a voice, but I never believed her. I painted, drew, and did stage crew, which gave me an outlet to express my emotions and was my first glimpse into theater and performance.

I first learned to “perform” for others through games like Rock Band (I was always on bass or vocals) and also on online chat games like Coke Studios, where the premise was to design a personalized avatar, write sample-based and electronic music, and share that music with strangers in chat rooms. It’s not far off from what I do now. Oh, I also played Sims Superstar—if that helps put me into context.

This ability to perform “in a game” and further “as someone else,” via a Sim or chat room avatar, helped me better confront my insecurity about singing and performing in front of others. The separation of identity and the ability to be whoever I wanted was a freeing perspective to have.

In art school, I participated in a noise-pop group called Phoot Phetish (which later transformed into Neon Black). I played bass (which I taught myself thanks to the internet). The simplicity and experimentation with sound was exciting to me. Noise (the genre) breaks down song structures; it gets to the heart of performance. It is often aggressive and political. At the same time, I’ve always been drawn to great pop stars like Whitney Houston and Britney Spears, and the immediacy of pop music. What if pop music could tell us something more? What if it could be used as a tool to expose its infrastructure and comment on our current time, using language that is approachable? Frankly, Noise is pretty hard to get into.

Klypi is described as an alien trapped on Earth, is a character that uniquely explores themes of identity and emotion. What parts of yourself do you see in Klypi, and what does this character allow you to express that you might not be able to as AC Carter?

AC: The parts I see in Klypi that I normally don’t express so forthrightly are gender identity, anger and revenge, and being able to voice a point of view.

Because Klypi is an alien, similar to Ursula K. Le Guin’s The Left Hand of Darkness, so they don’t have gender. Not only does Klypi allow me to further express my gender fluidity (or non-binary-ness), but they can also inquire and reveal the sexism that is inherent in American society. Why is my sex perceived as inferior?

Klypi is granted a whole new list of emotions they never felt on their home planet. The script was different. These new emotions are met with investigation and excitement through songwriting. However, there’s also a lack of control with those emotions, equating to bombastic sounds, and in my live performance, a lot of screaming.

Klypi falls in love with humans, gets abused by humans, has to get a job like humans, and is left sad through it all. How do they confront these feelings? Is this new life on Earth really all it’s cracked up to be? Should they have stayed home? (This in and of itself lets me think of my own experience leaving home to pursue a better life.)

Klypi is opinionated, confrontational, but also really sweet. They give off Gremlin energy. As myself, AC, I’m pretty pragmatic and understanding, but Klypi on the other hand, will be in your face, such as in songs like “Get the F*ck Away From Me.” Klypi channels my anger—constructively.

“Icon Enterprises” marks a big step in your career. What was the main inspiration behind the album, and is there a theme, experience, or feeling within the record that you feel best captures its essence?

AC: It IS a big step! This is my first release on VINYL, too 🙂 I’m very thankful. Thank you, Lollipop!

The main themes are unrequited love, abuse, capitalism, feminism, and queer confrontation and celebration, depending on the track.

It’s pretty diaristic, yet these experiences aren’t singular to me. Stating my experiences vulnerably is the best way I know how to write—at least right now. It’s pent-up anger, it’s sadness, it’s being alone in your room and reaching out to the internet to talk to someone who will finally GET you. It’s desperately wanting to be accepted for who you are, and even when you are still the freak, it’s strength in knowing who you are and not abandoning yourself. It’s telling a joke to make yourself feel better, and then scream-crying after.

The album delves into topics like abuse, digital disconnection, isolation, and unrequited love, among others. How important was it for you to open up about these personal experiences, and how cathartic or freeing did it feel to turn them into music?

AC: Being able to state something that is hard and to be heard is so powerful, especially in channeling rage. And being able to put that rage into melody becomes something so momentous and stimulating. I’m thankful I have that inclination—that need to create.

Being able to make art from my experiences, especially the sad ones, helps me release that pain and hopefully connect with others who have gone through the same thing.

Of all the songs on “Icon Enterprises”, is there one that feels especially meaningful to you? What’s the story or message behind it?

AC: Hmm, this is a hard one. Maybe it’s “Dumb Crush”. Songwriting-wise, it was the first song where the melody and words came first. I typically write in a DAW (Digital Audio Workstation), so I write a bassline and drum beat first before a vocal melody, but this one was an a cappella riff that came into my head while walking home after attending a show. I saw a band whose very attractive front person made me feel immediately smitten. I knew it was completely “dumb” though— as a performer, I know I can confuse my infatuation with the performance with who the person is. Instead of doing what I’ve done in the past—getting myself mixed up with someone who is “unavailable” in more ways than one—I left the show early humming “I got a dumb crush on you / And I don’t know what to do / Are these feelings even true? / I got a dumb crush on you…” I felt zapped by the songwriting gods—this was a good riff, this was a good tune.

Funny enough, most of my best lyrics come from when I’m not trying to write—going for a walk, cooking, taking a shower—those are the moments where I can mind-wander without constraint.

I had just moved to LA, was excited about any future potential, and I needed to change how I confronted romance. I think the bridge lyrics reflect my insecurities around these feelings towards anyone I become interested in: “Sometimes I think less of me / Don’t deserve someone lovely / I anticipate they’ll hurt me / It’s been my history!”

And, it was also the hardest song for me to produce. It’s a testament that sometimes an idea should be reworked over and over until it makes sense to move forward. From this song, I gained more confidence in different ways of writing.

Through “Icon Enterprises”, it seems like you’re reaching out to listeners who may have experienced feelings of isolation, disillusionment, or confusion in today’s world. What’s the main message you hope listeners will take away from the album?

AC: You are not alone. Don’t change who you are just to fit in!

Your music and lyrics often reflect the clash between staying true to oneself and the values of a world that can be indifferent or resistant to difference. How does “Icon Enterprises” address this struggle, and how do you see Klypi helping to normalize these themes within pop music?

AC: Like a lot of kids, I wanted to be accepted. But I wanted to be accepted for who I was—even if I was weird or different. Even as an adult who is secure in themselves, I still have fallen victim to trying to fit into a mold that wasn’t for me. Like, what could I do to make a lover actually want to be with me? Was I not ______ enough? And then whatever that void was, I’d try my best to BE that.

I think there’s this idea that artists are 100% completely sure of themselves because they put themselves out there confidently—branding can create that idea. But there’s a person beyond that. Kinda like the Wizard in The Wizard of Oz. I’m still pretty shy, and I can be so critical of myself.

Klypi isn’t trying to be cool. They’re just trying to be themselves, and I think that’s a positive message to share. Why be normal? What even is “normal” or “cool” anyway?

Your sound is influenced by ’80s synth-pop, but with a very contemporary twist. What does this sense of retro nostalgia mean to you, and how do you think this aesthetic enhances the Icon Enterprises experience?

AC: 1981 to 1989: Reagan was in office. Now, Trump has been re-elected for a second term. To me, ’80s synth-pop was inherently political. It was a response to Reaganomics, Thatcherism, and classism. It was a time when music communicated serious issues but in an upbeat, catchy way. Think of Madonna’s “Material Girl,” where she satirizes wealth and extravagance. How can I embrace that ethos while using contemporary sounds to build something new—a more inclusive and open-minded future?

The ’80s sounds were so futuristic—round, bouncy, bright. They were boxy and glittery, dark yet optimistic. “Hyper” even, for the time.

Visually, the album design pays homage to the era of floppy disks, vintage tech, and office aesthetics. How does this visual style connect with the themes of the album, and why was it important for you to mix nostalgic elements with such personal, modern topics?

AC: I’ve always had a soft spot for vintage office aesthetics—the beiges, the greys, the boxy designs, the grainy textures of broadcast equipment that typically documents it. There’s something about those small pops of color in old logos and the fact that this older tech used to be “futuristic.” If you’ve ever seen 9 to 5 with Dolly Parton, it sums up the feminist angle of my work.

I also wanted the title of my diaristic “mixtape” to be a form of data sharing that is similar to the vinyl record but from a satirical corporate point of view. “Icon Enterprises” is the title satirically and phonetically used the name of Carl Icahn’s company, “Icahn Enterprises”, which is a conglomerate company created in the 80s that is run by an investor who has stated, “Part of my values is to make money, and I can’t change my values. I mean, some people love art, you know, love to paint. If a great painter loves to paint, well, you can’t – what do you do, criticize him because he likes to paint?”

This was hilarious to me. Another terrible man weaponized being an artist. Sorry, Carl, but you were a man interested in helping corporations and rich people. He was against Unions. He supported Reagan. He was a jerk.

A floppy disk technically has a disk inside a hard casing. Additionally, the floppy disk cover art was first done by designer Peter Saville for New Order’s single “Blue Monday”, however with die-cutting and reformatting. I decided to use the 3 ½ inch Floppy Disk which is used as a literal icon on any computer to symbolize the “save” action, which as Klypi, whose name also comes from both a symbol and Windows Office Assistant in the 90’s, made the most sense. I also took the emoji of the floppy disk into mind.

Last, I’m drawn to these elements because I can use them as both a tool and a metaphor to critique a classist and patriarchal system in America. At the same time, I find beauty in the objects that make up these spaces—spaces that people like me, as artists, don’t inherently belong to.

With “Icon Enterprises”, you’ve overseen every creative detail—from the music to the visuals and the live performance design. How important is it for you to maintain this creative autonomy, and how do you hope this multidisciplinary work will resonate with your audience?

AC: I think my work is at its strongest when I’m involved in every aspect. Not only did I write and record the songs, but I also designed and chose the visual language, the symbolism, and the ongoing storytelling. With Klypi, I’ve been able to design the outfit (collaborating with a cycling company), create the backstory, incorporate metaphors, and bring the whole vision to life.

For now, this holistic approach feels necessary for my practice. It might not be the same for every artist, and I have found some really great and real ways to collaborate with other artists, but for now, taking control of most aspects allows me to play to my strengths while thinking about Klypi in a broader, multidisciplinary way.

Now that “Icon Enterprises” is out, do you have any upcoming projects or new directions you’re exploring? What can fans expect from you next?

AC: I’m releasing a music video for “Dumb Crush” that’s directed by Joe W. Sams, hopefully this month (November). I’m still figuring out the premiere date—stay tuned!

I’ll also be performing on December 4th at Gold Diggers in LA with Gelli Haha and Dance Arts Center, which I’m really excited about. Then, on December 14th, I’ll be performing at Joe’s art show WAVELAND in LA (he also shot my video for “Dumb Crush”) alongside Active Decay. Another show I’m pumped for!

In January, I’m releasing a cover of Depeche Mode’s “Everything Counts.” It’s very anti-capitalism, anti-Trump, anti-corporate greed, and anti-economic disparity.

I’m also writing a screenplay for an interview between Klypi and another persona of mine, Vixcine Martine, who’s a PhD student in Contemporary Art Herstories. Vixcine will interview Klypi at MOCA (in a green-screen style), asking pointed questions about who Klypi is and who I am, as well as exploring other themes that I feel need to be addressed now. It’s inspired by Laurie Anderson’s video piece, “What You Mean We?”, where she’s interviewed alongside her clone.

Lastly, I’m working on a tour for 2025. More to come 🙂

photos / Vic Binkey

CONNECT WITH KLYPI